Pipelined proving

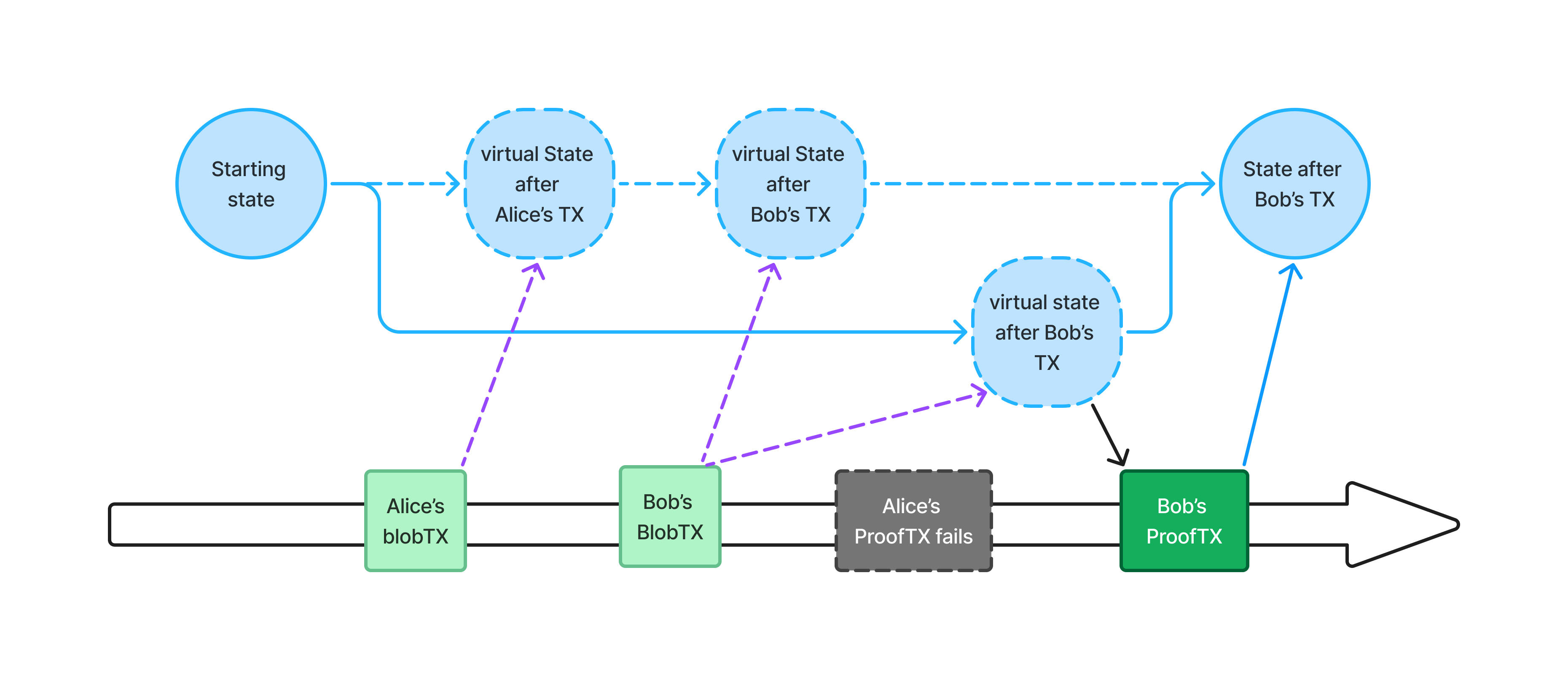

The problem: base state conflicts

The Hylé base layer ensures both privacy and scalability by verifying only the state transitions of smart contracts, rather than re-executing them. This approach reduces computational overhead but introduces a critical issue for provable applications: base state conflicts.

An app with a lot of usage will see conflicting operations, where multiple transactions reference the same base state, waiting for the previous state change to be settled.

The time spent generating proofs delays transaction finality. Proofs require accurate timestamps, but users can't predict when their transaction will be sequenced.

This causes parallelization limits: multiple transactions may reference the same base state, creating invalid proofs when one is settled before the other.

We solve these issues by splitting sequencing from settlement; an operation includes two transactions.

Blob- and proof-transactions

Read more on the content of blob and proof transactions on our transaction page.

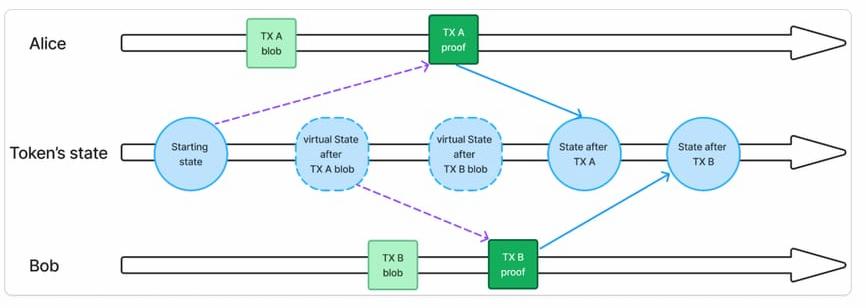

To address base state conflicts, Hylé splits operations into two transactions:

- Blob-transaction: outlines a state change for sequencing.

- Proof-transaction: provides a proof of the state change for settlement.

From Hylé’s perspective, the blob-transaction's content does not matter: it simply represents incoming information that your contract will process. For a developer, sequencing provides you with a fixed order and timestamp before proving begins. Once the transactions are sequenced, the provers can easily know upon which state they should base their proof. As a developer, you can also decide on how much information is disclosed in your blob-transaction: this is app-specific.

Settlement happens when the corresponding proof transaction is verified and added to a block. During settlement, unproven blob transactions linked to the contract are executed in their sequencing order.

This separation solves all three issues shown above. The blob transaction immediately reserves a place in execution order, allowing proof generation to run without blocking other transactions. The sequencing provides an immutable timestamp, so provers know which base state to use when generating proofs and can parallelize actions.

Unprovable transactions

Even with pipelined proving, sequenced transactions that never settle can slow down the network.

To remove this risk, Hylé enforces timeouts for blob transactions.

Each blob transaction is assigned a specific time limit for the associated proof to be submitted and verified. Subsequent transactions can proceed without waiting indefinitely.

Failed transactions

If the proof isn't submitted before timeout, or if the submitted proof is invalid, the transaction is included in the block, marked as Rejected, and is ignored for state updates.

The inclusion of the unproven transaction in the block ensures transparency, as the transaction data remains accessible.